Is hydropower good or bad for the environment? We went to Idaho to find out

- Share via

What’s more important: Tearing down dams that have decimated rivers and driven salmon and other fish toward extinction? Or letting those dams stay up, so they can keep producing carbon-free electricity that doesn’t worsen the climate crisis?

That question has been on my mind since April, when I spent a week in Idaho exploring the pros and cons of hydropower.

Along with its Pacific Northwest neighbors, the Gem State gets more power from dams than anywhere else in the country. Utility company Idaho Power intends to use those dams as the backbone of its voluntary pledge to achieve 100% clean energy.

You're reading Boiling Point

Sammy Roth gets you up to speed on climate change, energy and the environment. Sign up to get it in your inbox twice a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

So should Idaho Power be seen as a model of sustainability? Or a river-destroying villain?

I’ve got some thoughts in Part 4 of Repowering the West, published this week. You can read the story here.

To report the story, I traveled with several L.A. Times colleagues — photographer Robert Gauthier and videographers Maggie Beidelman and Jessica Q. Chen — up and down the Snake River, from a series of dams along the Oregon border to a spectacular canyon south of Boise. We explored the proposed site of Idaho’s biggest wind farm and farm fields powered by solar panels.

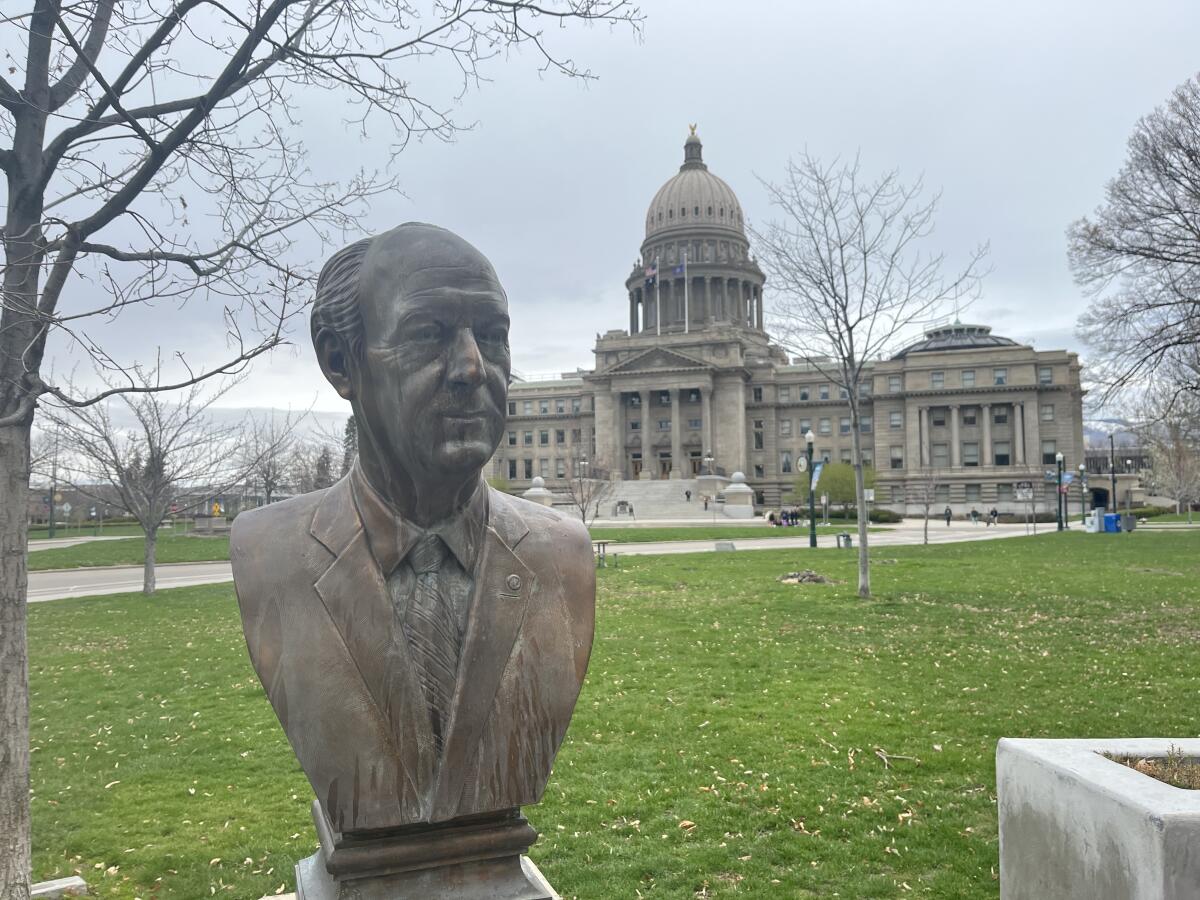

Before the rest of the team arrived, I spent a few days at a Society of Environmental Journalists conference in Boise, where several speakers made the case that Idaho is a purple state politically. Despite its conservative bona fides — nearly two-thirds of voters chose Donald Trump for president in 2020 — Idahoans love their great outdoors, their rivers and wilderness preserves and hunting grounds. An educational display outside the State Capitol honors former Gov. Cecil Andrus for his conservation work.

So maybe I shouldn’t have been quite so surprised in 2019, when Idaho Power announced it would target 100% climate-friendly energy by 2045. Lisa Grow, the company’s chief executive, told me that elected officials “trust us to run our business.”

“The governor came out in a press conference and said, ‘Gosh, if they can do this and make it reliable and affordable, we support it,’” Grow said. “They just traditionally haven’t felt the need to intervene and force us into doing something.”

Contrast that with Wyoming, where lawmakers have slammed renewable energy as costly and unreliable. Or Montana, where the legislature recently attempted to bar state officials from considering climate consequences before approving new gas plants.

There’s at least one difference between Idaho and those conservative bastions: The Gem State has hardly any fossil fuel industry.

Idaho produces no coal, not much oil and less natural gas than all but seven states. Gas accounted for just 12% of Idaho Power’s electricity last year. And although the utility gets about 20% of its power from coal plants, all of them are in other states.

Which isn’t to say that Idaho Power loves all forms of renewable energy — or that blue-state utilities do, either.

After a decade of prodding from monopoly utility companies Southern California Edison, Pacific Gas & Electric and San Diego Gas & Electric, California officials voted last year to slash incentive payments for rooftop solar power. The utilities made the case that lower-income families are paying higher electricity rates to subsidize homes that can more easily afford solar — an argument that won support from consumer advocates, but which many environmentalists consider a thinly veiled excuse to pad utility profits.

Utilities in other states have won similar cuts to rooftop solar incentives. And now Idaho Power is trying to join the party.

Environmental activists are furious. In a recent opinion piece for the Idaho Statesman, three high school seniors from the Idaho Climate Justice League told Grow that she’s in “in a position of power to help make or break Idaho’s future.”

“Are you going to prioritize people and the planet or shareholder profits?” they asked.

Russ Schiermeier is more sympathetic to the utility company — but still concerned about the future of solar.

Schiermeier grows alfalfa, peppermint, wheat and more on 3,400 acres in southwestern Idaho, using water pumped from the nearby Snake River. He’s been farming since 2008, when he bought ground that he describes as “some of the worst soil you’ll ever find” and began experimenting to improve its health. He built a house where he lives today with his wife and three daughters, the youngest of whom — age 5 — joined him in the seat of his combine last year as he harvested hundreds of acres of corn.

One reason he’s been able to make the economics work? Solar panels.

An engineer by training, Schiermeier designed and installed nine ground-mounted solar systems across the property. He was excited to show them off when I visited, grinning as he stepped beneath a canopy of gleaming black panels casting shadows on the bare dirt as they tilted toward the sun. To his mind, they’re just another crop, converting sunlight to a usable form.

“I’ve got 3,000 acres of organic solar panels. I just have 15 acres of nonorganic ones,” he said.

Solar panels have cut Schiermeier’s annual electricity bills roughly in half, from $300,000 to $150,000. The net metering incentive program — which Idaho Power wants to slash for some customers — has improved the economics, by compensating Schiermeier for electricity he contributes to the grid. He’s close to making back his up-front investment of around $2 million.

Schiermeier understands Idaho Power’s need for “a fair shake, where they’re making their fair share” of profits. At the same time, he said, solar systems like his can help the state stay powered during heat waves — especially as Boise continues to grow.

“Why aren’t we putting money in Idaho where it’s going to pay off in the long run?” he asked.

When I asked Grow about rooftop solar, she made the usual utility arguments — that net metering burdens poor families, that the technology will mature and grow on its own, that Idaho Power needs resources it can control to ensure the lights stay on.

Whether those claims are valid or bunk, utilities such as Idaho Power have a crucial role to play in confronting the climate crisis. Researchers have found there aren’t nearly enough rooftops to replace all the fossil fuel that America currently burns.

To be clear: The more small-scale solar, the better. More solar on rooftops and farms means fewer sprawling solar fields, towering wind turbines and long-distance transmission lines that can damage the environment and spur time-consuming battles.

It also means less need for destructive hydropower dams, at least on the margins.

All of which brings us back to the Snake River.

Our third night on the road, we stayed in a tiny town built by Idaho Power along a bend on the Snake, near Oxbow Dam. We ate a family-style dinner at the mess hall, with delicious cherry pineapple cake for dessert, then retired to the guest house.

Early the next morning, I couldn’t help but feel impressed as we toured Hells Canyon Dam. As much as I understood the damage this artificial river-stopper had done — the dead fish, the devastated tribes, the dramatically altered views — I found it strangely entrancing. The way the concrete wall brought the river to a sudden halt. The intricate engineering inside the power plant. The water flowing gently out of the dam and toward the Pacific, unnaturally calm but undeniably peaceful.

For a full rundown of the harms caused by dams — and hydropower’s role in limiting climate change — read my story.

But I’ll tell you right here that I feel conflicted.

Slashing fossil fuel combustion is the most important thing we can do to build a safer world for humans, animals and plants. Hydropower dams can help on that front. The fewer we tear down, the easier it will be to stop burning coal, oil and gas.

At the same time, though, I know my perspective is limited.

Truth be told, I am not much of a river person.

Don’t get me wrong — I love looking at rivers, and I realize how important they are for supplying drinking water and ensuring a healthy planet. But I’ve never once gone fishing. Or river-rafting. My ancestors didn’t structure their lives around salmon.

So it was easy for me to spend a week running around Idaho and finding myself gravitating toward the idea that dams are more good than bad because they’ve positioned the biggest power company in a deep-red state to go green.

It would have been a lot harder if I’d had anything resembling a real relationship with the Snake River.

Daniel Stone, environmental program director at the Upper Snake River Tribes Foundation, does have such a relationship. He’s an enrolled member of the Shoshone-Bannock Tribes, and he told me Snake River salmon were “central to the lifeways” of his people and others for thousands of years, as the fish “maintained the ecological abundance that helped our people thrive.”

“Our people lived with the pulse of that river,” Stone said.

But a lot has changed since the era of dam-building obliterated salmon populations.

“You can’t imagine the effect that is has on a tribal people to go from having access to abundant and sustainable food sources — bringing nutrients from the Pacific Ocean to the high deserts and mountains of the Columbia River basin — to having no access to salmon within a couple of generations,” he said.

Stone is right — I can’t imagine that. I’ve never experienced it.

So how do we strike the right balance? Between the clean energy dams produce and their continued legacy of harm?

I don’t have a simple answer.

But I do think that in an era of climate calamity, the answer is more complicated than “dams are bad.” Just like it’s more complicated than “solar projects are good” or “electric lines are ugly” or “farmers use too much water,” to refer back to previous stories in The Times’ Repowering the West series. There are tough choices ahead of us. None of this will be easy.

Some environmentalists, though, have managed to find common ground with the hydroelectric industry.

Two years ago, I wrote about conservation groups including American Rivers and the World Wildlife Fund partnering with the National Hydropower Assn. They had asked the federal government for $63 billion to fund safety improvements at potentially hazardous dams and tear down 2,000 others — and, crucially, produce more hydropower at dams that would stay up.

The unusual coalition — which grew out of a dialogue convened at Stanford University — has won support on Capitol Hill.

The bipartisan infrastructure law passed by Congress in 2021 included $2.3 billion to upgrade some dams and remove others. President Biden’s 2022 climate law, the Inflation Reduction Act, established a 30% tax credit for adding hydropower turbines at dams without them. And Sen. Maria Cantwell (D-Wash.) joined with Sen. Steve Daines (R-Mont.) this year to introduce a bill that would speed up licensing to add hydropower at existing dams — and make it easier to remove dams that are no longer needed.

The bill’s supporters include the National Congress of American Indians, because it would increase the role of tribes in licensing.

“The support from the left, from the right and the center is remarkable,” Daines said at a July hearing.

“Hydropower is critical to helping meet our country’s energy needs,” he added. “It’s safe, reliable, affordable.”

Is he right or wrong? Or is the truth somewhere in the middle, in that murky space between red and blue and green?

Reply to this email to let me know what you think. I’ll include some responses in a future Boiling Point newsletter.

But before you sound off, read Part 4 of Repowering the West. And if you can, subscribe to The Times to support our journalism.

ONE MORE THING

Some big news here at the Los Angeles Times: This week, we’ve launched a new and expanded climate change section!

Dubbed “Climate California,” the new section brings together a dozen environment, science and health reporters from across the newsroom, myself included. More details here on who’s involved and what each of us will be focused on. Already this week, we’ve got a bunch of important stories that we’d love for you to read, including this one about the 1 million Golden State residents who still lack access to clean, safe, affordable drinking water, and this one about the land barons of California’s Central Valley.

Stay tuned for more in the next few days, including stories on the long-awaited removal of Klamath River dams, the value of plug-in hybrid vehicles and the desperate need for more shade — and maybe fewer palm trees — in Southern California cities.

One more thing: As part of the new section, I’m becoming The Times’ first climate columnist. Which I’m excited about!

In practice, what you can expect from me won’t change too much — I’ll keep writing Boiling Point twice a week, with a focus on clean energy and occasional forays into other topics. And I’ll keep telling you how I’m thinking about the possible climate change solutions at our disposal, while sharing plenty of perspectives besides my own — as long as they’re grounded in reality.

As always, feel free to reply to this email with your thoughts, questions and suggestions. I want to hear from you.

We’ll be back in your inbox Tuesday. To view this newsletter in your Web browser, click here. And for more climate and environment news, follow @Sammy_Roth on Twitter.

Toward a more sustainable California

Get Boiling Point, our newsletter exploring climate change, energy and the environment, and become part of the conversation — and the solution.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.