Russian village is still paying the price for Chernobyl disaster

After the Chernobyl catastrophe the authorities replaced all the old water wells in Stary Vyshkov with one artesian well, a water-pressure tower and a system of water fountains. But electric power is very often cut off and that cuts off the water supply too. In summer, even with power on, water pressure is not sufficient. These old women complain of very low water pressure as they are trying to fill a bucket. (Sergei L. Loiko / Los Angeles Times)

Andrei Zhdanovich, 42, a former collective farm worker, drinks beer to kill his hangover next to his abandoned house in the village of Stary Vyshkov. (Sergei L. Loiko / Los Angeles Times)

Svetlana Plakhotina, a former milk woman at a local collective farm, at 41 has terminal

In the Komsomolets collective farm based in Stary Vyshkov, only about 200 emaciated cows out of the former 4,000-head herd remain. Their radiation-contaminated milk is processed into butter or mixed with cleaner milk from other collective farms, an official said. (Sergei L. Loiko / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

Schoolteacher Tatiana Gudzikevich, 44, takes stock of her family’s food preserves. They mostly eat food they grow themselves in the radiation-contaminated soil of Stary Vyshkov. Preserving home-grown foods lowers radiation, she says. (Sergei L. Loiko / Los Angeles Times)

A man plows radioactive land abandoned by the local collective farm near the village of Stary Vyshkov. (Sergei L. Loiko / Los Angeles Times)

Svetlana Ivanova stands near her husband’s grave in the cemetery of Stary Vyshkov. Her husband Pyotr Ivanov, a former collective farm tractor driver, committed suicide. She says he was in stress because they couldn’t get enough money to go away from the radiation-contaminated zone. (Sergei L. Loiko / Los Angeles Times)

Children play inside a deserted house in Stary Vyshkov. About two thirds of the houses in the village are abandoned, ruined and looted. (Sergei L. Loiko / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

Svetlana Ivanova, 49, a resident of Stary Vyshkov, admits that sometimes she wakes up at night and thinks about taking her life. Her husband Pyotr Ivanov, a former collective farm tractor driver, committed suicide. She says he was in stress because they couldn’t get enough money to go away from the radiation-contaminated zone. (Sergei L. Loiko / Los Angeles Times)

Ruins of a collective farm near Stary Vyshkov. (Sergei L. Loiko / Los Angeles Times)

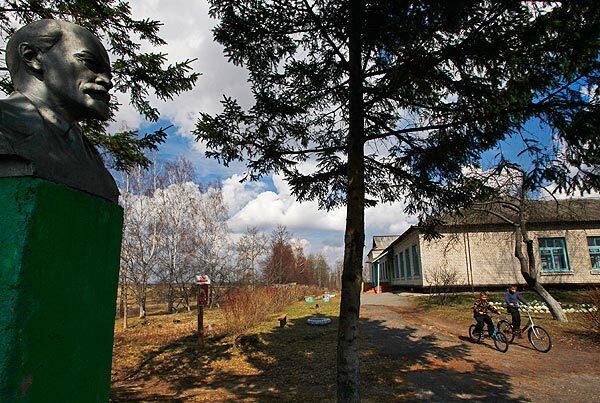

A monument to Lenin next to the school building in the village of Stary Vyshkov is the most radiation-contaminated spot around the school, experts said. (Sergei L. Loiko / Los Angeles Times)

Nadezhda Korotkaya, 77, has lived in this village through World War II and the Chernobyl catastrophe. “Germans came and went but Chernobyl came to stay,” she says. (Sergei L. Loiko / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

Old women walk along the street of Stary Vyshkov. (Sergei L. Loiko / Los Angeles Times)

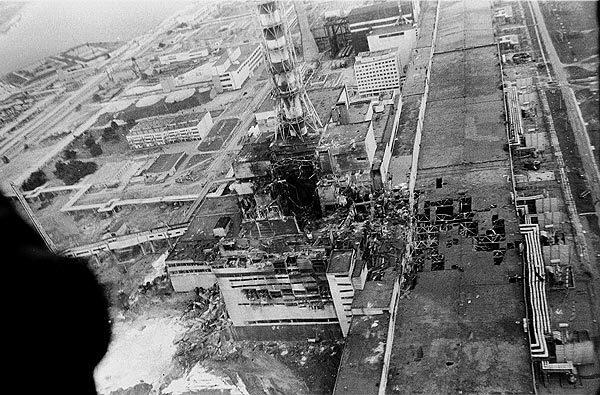

This May 1986 file photo shows the Chernobyl nuclear power plant, the site of the world’s worst nuclear accident. Twenty-five years ago, power plant exploded in Ukraine, spreading radioactive material across much of the northern hemisphere. The April 26, 1986, explosion affected about 3.3 million Ukrainians, including 1.5 million children, according to Ukraine’s Chernobyl Union report. The plant was closed for good in 2000. (Vladimir Repik / Associated Press)