Photos: Bullfighting in Spain

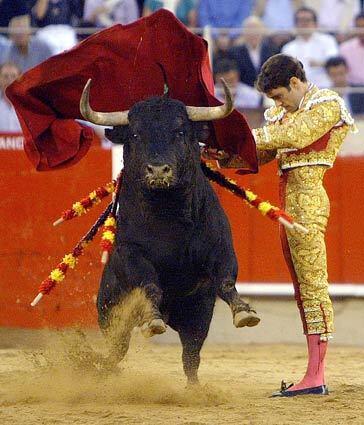

Matador Jose Tomas, at work in Barcelona in September, has revived a passion for bullfighting in Spain. (Cesar Rangel / AFP-Getty Images)

After an abrupt and unexplained retirement in 2002, Jose Tomas made a dramatic comeback this year to accolades bordering on hysteria. Across Spain, politicians, artists, musicians and ordinary fans rejoiced. Half-empty arenas gave way to packed stands. (Cesar Rangel / AFP-Getty Images)

Jose Tomas performs in Barcelona in 2007 to a sellout crowd, the ring’s first in 22 years. Tomas deliberately chose to make his return in Barcelona, where anti-bullfighting sentiment is especially strong. (Cesar Rangel / AFP/Getty Images)

The adulation in Spain for Jose Tomas has to do with what aficionados see as his unparalleled bravery and artistry. He manages to evince an air of commanding calm, even when hes been gored by a bull and is bleeding profusely, struggling not to pass out. (Cesar Rangel / AFP-Getty Images)

Advertisement

The great Spanish bullfighter Manuel Laureano Rodríguez Sánchez, better known as Manolete, who died in the bullring in 1947, after being gored by a bull. (AFP/Getty Images)

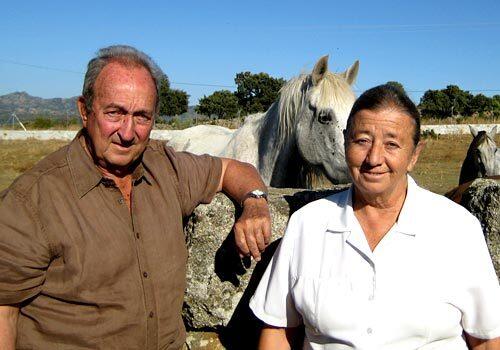

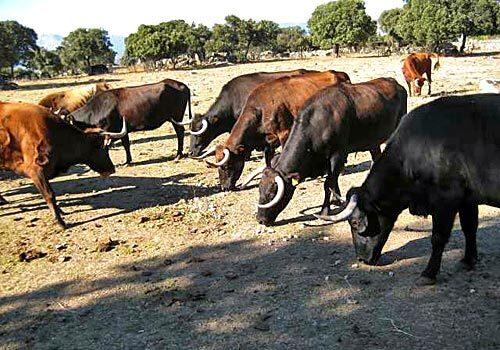

Juan Jose Rueda and his wife, Luisa Parache, have been raising fighting bulls for generations. Their ranch in Galapagar, Spain, has been in their family for a couple of centuries. The bullfighting season lasts from March to October, with an estimated 2,000 events involving the killing of at least 12,000 bulls. (Tracy Wilkinson / Los Angeles Times)

Animal rights advocates and other critics say the bullfighting industry institutionalizes, subsidizes and encourages cruelty, and creates a national tolerance for the abuse of animals. But bullfighting advocates, who include patrons as powerful as the king of Spain, point to the detailed choreography, costumes and music, all of which combine to create what they regard as a unique art form. (Tracy Wilkinson / Los Angeles Times)