Living on Kivalina

The Alaskan island of Kivalina looks like a giant tadpole from the air, with the Chukchi Sea to the left steadily lapping up the shoreline. Many believe global warming is taking its toll on the island and though there have been talks over the years of relocating its 400 residents, squabbles and uncertainty have derailed any long-term plans. (Don Bartletti / Los Angeles Times)

Jason Norton, 8, looks out his bedroom window at the workers filling sandbags for the sea wall that shields the island from the Chukchi Sea. Of the 70 or so houses in Kivalina that sit on short stilts, his is the closest to the steadily eroding beach. (Don Bartletti / Los Angeles Times)

It’s a calm afternoon on the shoreline, where workers position 2,500-pound sandbags for the sea wall. (Don Bartletti / Los Angeles Times)

The $3-million sea wall has been under almost constant repair since the day it was completed last October. Its like a bucket that keeps developing holes, says Colleen Swan, the island’s tribal administrator. (Don Bartletti / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

Joe Swan Jr. lifts a fresh caribou skin from a drying bar. Subsistence hunting provides meat for his family, but he feels extra lucky to have a job repairing the wall that pays $22.50 an hour. He says when he was growing up in the ‘70s, the ocean would freeze into a thick slush come fall and the waves would crash into the ice. Lately, there’s little change in autumn, leaving the eroded shoreline vulnerable to waves. (Don Bartletti / Los Angeles Times)

Work continues into the early night filling hundreds of massive sandbags. Crews stack the bags Monday through Friday but stop on the weekends because of a tight budget. (Don Bartletti / Los Angeles Times)

Small waves wash against the sandbags meant to keep the sea from encroaching. Recent storms have destroyed the reinforcements almost as fast as they can be put in place. About 10 to 15 more years remain before the ground beneath the clapboard homes washes away, according to estimates by the Army Corps of Engineers. (Don Bartletti / Los Angeles Times)

Kivalina’s former Mayor Austin Swan photographs the progress on the sea wall project. He and the vice mayor were voted out of office in October amid complaints of job shortages and the lack of progress on relocating the island. (Don Bartletti / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

Life is mostly quiet on the main street of the isolated village, which was once an occasional hunting camp for the Eskimos before the U.S. government started building a settlement in 1905. Today, there is little work in town and most homes have no running water and the standard toilet is a 5-gallon bucket. (Don Bartletti / Los Angeles Times)

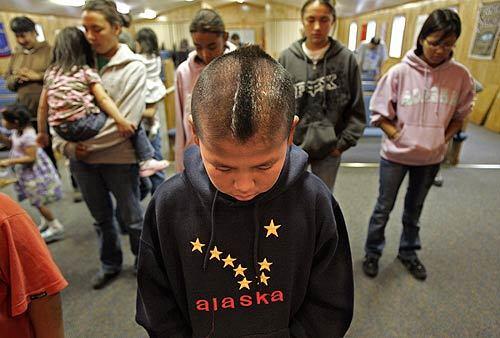

Youths bow their heads for a special blessing by pastor Lowell Sage during Sunday services at Friends Church. (Don Bartletti / Los Angeles Times)

Geese fly over two cold cellars that are marked by sticks used to raise and lower food into the ground. Usually, the permafrost acts like a natural freezer, preserving meat and fish all summer. Recently however, warmer summers have caused some of the cellars to thaw and fill with water. (Don Bartletti / Los Angeles Times)

Austin Swan checks the condition of a cold cellar dug about 12 feet into the permafrost. Buckets hold fish, caribou and whale meat that will be preserved and aged through the summer. The icicles are evidence of the frozen ground’s partial thawing. (Don Bartletti / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

Villagers team up to gather the fish caught in their nets on the Wulik River, about 10 miles upstream from Kivalina. Native people have been fishing and hunting in the unspoiled tundra for generations. (Don Bartletti / Los Angeles Times)

Standing knee-deep in the frigid water, Lowell Sage lifts a full-grown salmon from his net on the Wulik River. The village pastor is worried that erosion will ultimately force Kivalina residents to be relocated far from their traditional hunting grounds. “You take hunting, fishing, gathering away, you take our culture,” he said. (Don Bartletti / Los Angeles Times)

Austin Swan walks through the cemetery that marks the generations of his family that have lived and died in Kivalina. For years, village leaders have squabbled with state and federal officials over relocation, but the high costs -- up to $250 million -- have put a damper on any plans. For the time being, sandbags remain the town’s only defense against the sea. (Don Bartletti / Los Angeles Times)