Lethal waste in New Mexico’s desert

Sunlight peeks through the clouds above the Los Alamos Neutron Science Center, part of the Los Alamos National Laboratory. More than 60 years after the lab’s scientists assembled the nuclear bombs dropped on Japan during World War II, lethal waste is seeping out of mountain burial grounds and moving toward drinking water sources. (Brian Vander Brug / Los Angeles Times)

Bulldozers move dirt on a hill above the Los Alamos Weir, which was designed to capture contaminant-bearing sediments and to allow runoff to pass downstream. Monitoring of runoff in canyons that drain into the Rio Grande has found unsafe concentrations of radioactive waste. (Brian Vander Brug / Los Angeles Times)

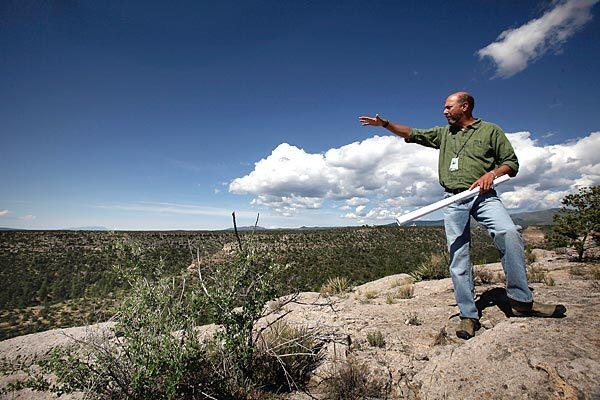

Danny Katzman, program manager for the Los Alamos National Laboratory’s water stewardship program, stands on a mesa overlooking Los Alamos Canyon. Though the type of waste that has been detected around Los Alamos can cause cancer, birth defects and other serious ailments, lab officials insist there is no jeopardy to human health. “We are seeing no human or ecological risk,” Katzman said. (Brian Vander Brug / Los Angeles Times)

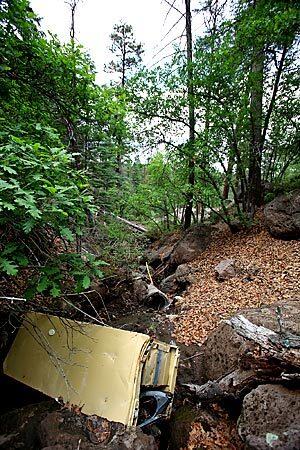

An old refrigerator and other debris litter aptly named Acid Canyon. The canyon was the dumping grounds for treated and untreated radioactive and hazardous waste from the lab’s first plutonium-processing building and waste-treatment facility. The canyon has since become a county park. (Brian Vander Brug / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

An outfall pipe lies in Acid Canyon’s South Fork. Many Los Alamos residents have become inured to their environment. They hike and picnic in canyons that are dotted with toxic hot spots. Radioactive waste was dumped for many years in Acid Canyon. (Brian Vander Brug / Los Angeles Times)

An ultrasonic water monitor has been set up in Pueblo Canyon, downstream from a new Los Alamos County water-treatment facility. A draft report released in June by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention states that the lab may have substantially underreported the extent of plutonium and tritium released into the environment since the 1940s. (Brian Vander Brug / Los Angeles Times)

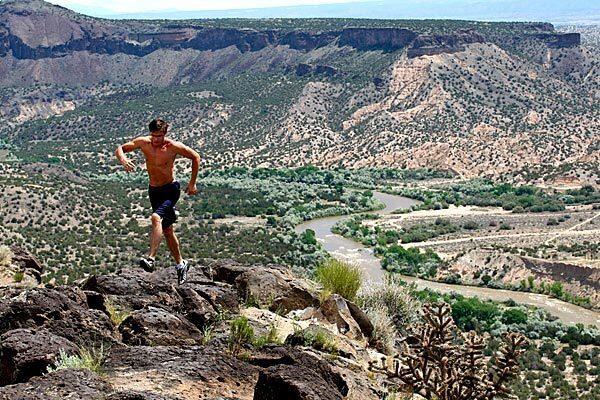

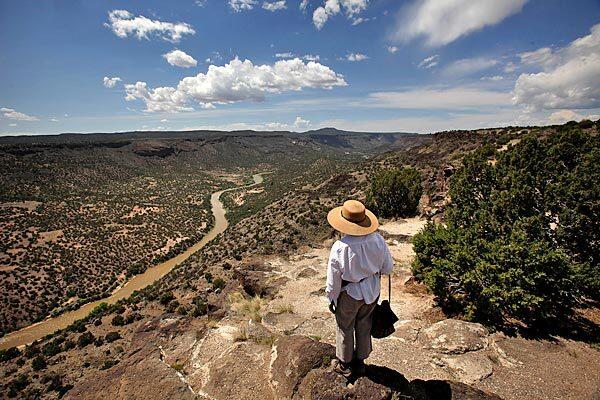

A runner ascends a hill at White Rock Overlook Park above the Rio Grande. So far, the level of contamination from the lab in the Rio Grande itself has not been high enough to raise health concerns. (Brian Vander Brug / Los Angeles Times)

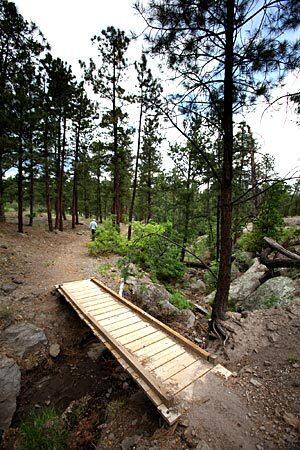

In 1967, the lab removed contaminated sediments from Acid Canyon and transferred the land to Los Alamos County. Now bridges traverse streams and hiking trails. (Brian Vander Brug / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

Geologist David Woody removes purge water from a Pajarito Plateau sampling well on the lab gounds. The lab is monitoring contaminants and their possible impact on the Los Alamos County water supply. (Brian Vander Brug / Los Angeles Times)

A canister of radioactive waste at the lab awaits shipment by truck to an underground storage facility operated by the U.S. Department of Energy in Carlsbad, N.M. (Brian Vander Brug / Los Angeles Times)

Susan Hazen-Hammond of White Rock, N.M., takes in the view of the Rio Grande from White Rock Overlook Park. Los Alamos and its environs may never be cleaned up entirely because of the longevity -- thousands of years in some cases -- of radioactive waste, according to an analysis by the National Academy of Sciences. (Brian Vander Brug / Los Angeles Times)