Dunbar Hotel

Originally called the Hotel Somerville, the building now houses 73 low-income apartments. City Hall will soon take ownership of because the hotel has failed to repay nearly $3 million in loans. (Gary Friedman / Los Angeles Times)

The hotel, financed by black business leaders, built by black craftsmen and opened along the spine of the black community, was a source of great pride in an age of segregation. (Gary Friedman / Los Angeles Times)

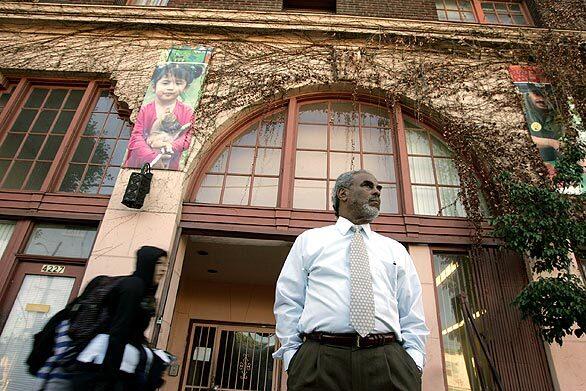

Michael Dolphin of the Dunbar Economic Development Corp. dreams to reopen the hotel to those who put it on the map: the musicians, mostly West Coast jazz artists, many of whom have grown old in anonymity. (Gary Friedman / Los Angeles Times)

The Art Deco lobby is still lighted by magnificent chandeliers, but the charm is mocked by cigarette butts and chewed up sunflower seeds on the window sills. (Gary Friedman / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

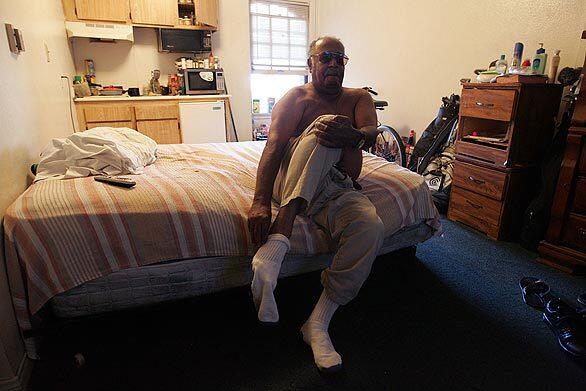

Jimmy Steward, 69, is one of 32 tenants at the Dunbar. He has lived there for 10 years and pays about $360 a month in rent. (Gary Friedman / Los Angeles Times)

Malcolm N. Bennett is a judge-appointed receiver of the hotel and is credited with improving living conditions and adding security. (Gary Friedman / Los Angeles Times)

The city expects to foreclose and put the hotel up for sale, but all parties assume that no one is going to buy. But even with a troubled present, its past is intact: “The Dunbar was the black version of the Ritz-Carlton,” one musician said. (Gary Friedman / Los Angeles Times)