Preservation: Frank Lloyd Wright’s Ennis House

The Ennis House,

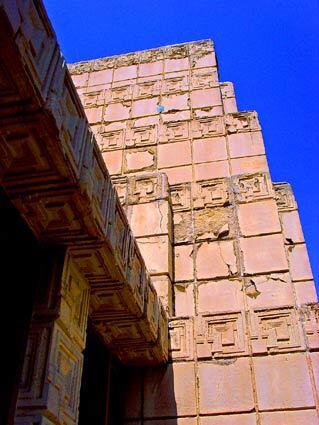

The home, which had long been a challenge to maintain, suffered a setback when sealer intended to protect the concrete blocks only hastened their disintegration. The 1994 Northridge earthquake further weakened the structure, as did record rainfall in late 2004 and early 2005, spurring the National Trust for Historic Preservation to list the site as one of Americas most endangered places. (Dale Kutzera / For The Times)

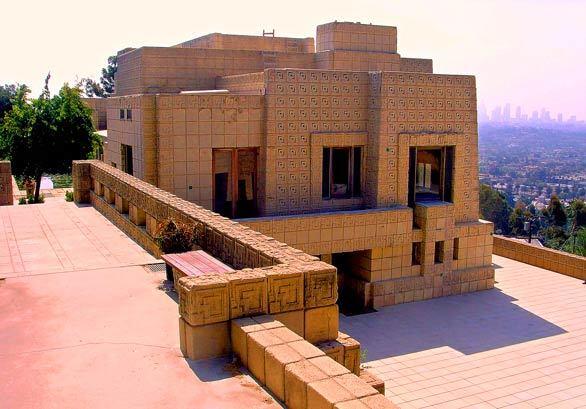

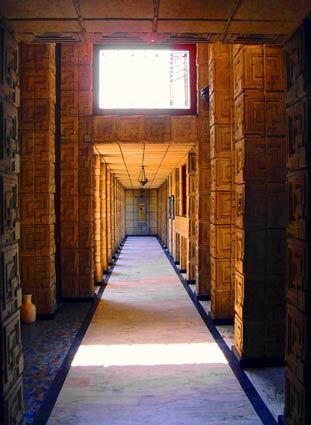

Ever since the house was built, it has dominated a promontory in the hills near Griffith Park like some sort of Mayan ruin. The intricately molded blocks define the inside of the house as well. Here, a long corridor serves as the spine of the home, with the master bedroom at one end and the kitchen at the other. (Dale Kutzera / For The Times)

Among the restoration work that has been completed: The roof has been replaced, conservation work has been performed on stained-glass windows, and the fireplace mosaic shown here has been repaired. The fireplace sits off a long corridor, across from the living room, where this picture was taken. The green square in the fireplace is a seismic survey tag, one of several that can be seen inside and out. (Dale Kutzera / For The Times)

Advertisement

The propertys last private owner, Gus Brown, purchased the house in 1968. He later created a nonprofit foundation that controlled and maintained the site after his Browns death in 2002. (Dale Kutzera / For The Times)

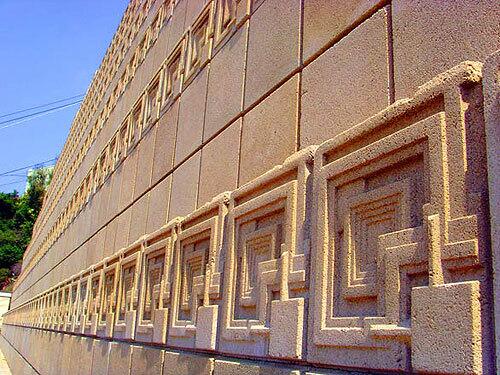

Winter rains four years ago posed the biggest threat to a wide motor court and monumental south retaining wall. When the wall disintegrated, the house was red-tagged. The motor court was taken out and new structural frame put up beneath it, said Linda Dishman, chairwoman of the Ennis House Foundation, the nonprofit group that owns the site. All of the concrete blocks that fell down have been replaced. (Dale Kutzera / For The Times)

The houses original blocks have been used to create molds for newly cast replacement concrete. The original blocks were never as structurally sound as Wright had expected, and even historical photos show buckles in the motor court and south wall. (Dale Kutzera / For The Times)

One of the lingering issues: public access. After Browns death, tours and events at the site tested the patience of neighbors. Some have suggested that when the Ennis House is ready to reopen, the foundation should offer tours only if they are limited in scope and free. Wed like to have public access, Dishman said. A lot of public money went into the house, and wed like to see if its possible to have public access in a way that is respectful of both the neighbors and fans of Wrights architecture. (Dale Kutzera / For The Times)