Bacteria strikes war’s wounded

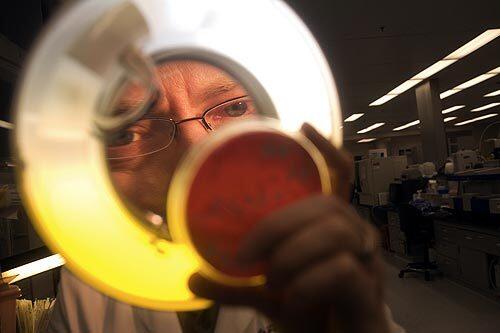

Dr. Kyle Petersen, an infectious disease specialist with the U.S. Navy, examines a colony of Acinetobacter baumannii at the National Naval Medical Center. Petersen was one of the first in 2003 to sound the alarm on an outbreak involving this unusual bacterium that was making the rounds among troops wounded in Iraq or Afghanistan. Years later, hundreds of patients in American military hospitals have become infected. (Dennis Drenner / For The Times)

Acinetobacter, although seen as a slacker in the bacterial world, is a persistent organism that is highly resistant to drugs. Once Petersen had made the Iraq-infected troops connection, he struggled to figure out how the bacterium had made its way into modern military hospitals. (Dennis Drenner / For The Times)

In the early days of the war, Petersen was a doctor aboard the hospital ship Comfort in the Persian Gulf that had so many infections in its intensive care unit that a nurse posted a sign: Acinetobacter Alley. At least 27 people infected with Acinetobacter have died in military hospitals since 2003. (Dennis Drenner / For The Times)

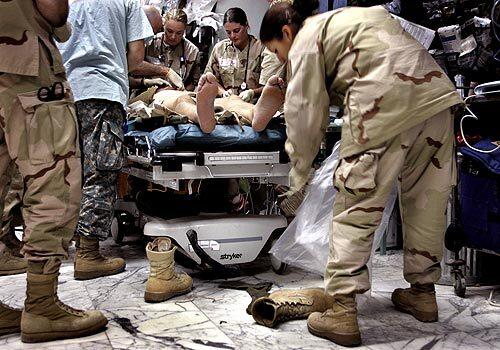

In ferreting out the cause of the infection, military researchers swabbed surfaces at seven field hospitals in Iraq and Kuwait, including parts of the hospital complex pictured here in Balad. Patient care areas in all seven field hospitals tested positive for the military strain of Acinetobacter. In such hectic environments, it was difficult to impose strict measures such as the thorough cleaning of hands and equipment, thus leaving the area vulnerable to the bug. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

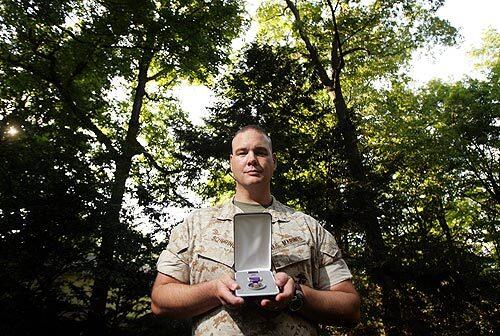

Marine Maj. K.C. Schuring holds his Purple Heart medal outside his Farmington Hills, Mich., home. Schuring, who was shot while on patrol in Ramadi in 2006, almost lost a leg to the bacterial infection. He said the treatment was like going through hell. Though he’s back at home, doctors warn that he must keep an eye out for any sign of the bacteria, which can lie dormant for years. (Rob Widdis / For The Times)