Wal-Mart in Guatemala

Wal-Mart Stores Inc. has unveiled a program in Guatemala to link more mom-and-pop growers to its supply chain. Working with the U.S. Agency for International Development and nonprofit groups, the American retail giant plans to train 600 farmers in the next three years to supply produce for its local stores. Here, a farmer works the fields in Chimaltenango. (Rodrigo Abd / For the Los Angeles Times)

Wal-Mart operates 457 Central American stores, including this Paiz supermarket in Chimaltenango, Guatemala. The American retailer says most of the fruits and vegetables its sells are produced locally. (Rodrigo Abd / For the Los Angeles Times)

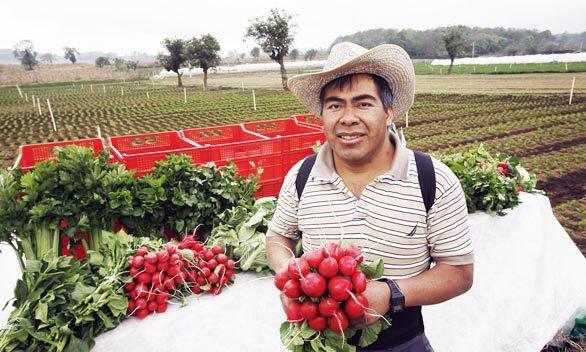

Wal-Mart has 40 agronomists on staff in Central America who work closely with farmers such as Fermin Pec, who grows radishes, lettuce, cabbage and other vegetables in San Pedro Sacatepequez. Their pickiness has helped me improve, Pec says of Wal-Mart’s requirements. (Rodrigo Abd / For the Los Angeles Times)

Wal-Mart seeks to diversify its supplier base to keep shelves stocked as it expands in Central America. The retailer, owner of this Paiz supermarket in Chimaltenango, Guatemala, also hopes to give small farmers the opportunity to produce niche items such as herbs that big growers won’t bother with. (Rodrigo Abd / For the Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

The success or failure of the Wal-Mart program and others like it may determine whether farm families like those in Chimaltenango can remain on their land amid the fast pace of change. Whats at stake for small farmers is that they may soon find they have no place to go with their produce, said agronomist Julio Berdegue, president of the Chile-based Latin American Center for Rural Development. (Rodrigo Abd / For the Los Angeles Times)

Farmworkers tend the fields in Chimaltenango, Guatemala. Wal-Mart hopes to recruit more small growers locally to address supply problems that have resulted in temporary shortages of lettuce and other products. (Rodrigo Abd / For the Los Angeles Times)

Wal-Mart is not the only global brand with a presence in the farm country of Chimaltenango, Guatemala. (Rodrigo Abd / For the Los Angeles Times)