Common Cause Should Turn to Grass Roots : Campaign-spending reform has less chance in the next Congress, but the electorate can be energized.

- Share via

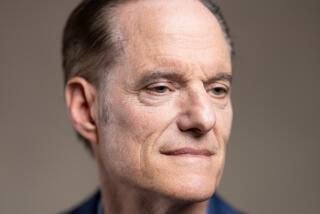

After 24 years at Common Cause, the past 14 as its president, Fred Wertheimer has decided to call it quits. Perhaps there will be a retirement party, a gold watch, a plaque for his wall. What he wants most, though, he won’t get.

Common Cause considers itself a watchdog of sorts, and although its efforts sometimes seem to coincide a little too neatly with the Democratic agenda, it has also been remarkably effective at drawing public attention to serious deficiencies in the American political system. It is possible to raise a bemused eyebrow about some of the organization’s proposed solutions, but the fact is, Common Cause, under Wertheimer’s leadership, has done yeoman service in pointing to the problems.

What Wertheimer wants most, at this point, is legislation changing the way congressional campaigns are financed. But Congress has gone home without acting, and now Wertheimer, too, is going home. His successor will get a chance to try again in the next Congress, but Republicans, who have very different ideas about how campaign finance laws ought to be changed, will be in a much stronger position then.

With a long record of success, however, Common Cause should not quit now. During the past 20 years, the organization has helped to end special-interest payments to congressmen in the form of speaking fees and has been a driving force behind a number of high-profile ethics investigations. The current system of financing campaigns is sorely in need of overhaul, and Common Cause, with its strong grass-roots lobbying arm, can play an important role in forcing reforms.

One important step would be for the organization to renew its commitment to its primary goal--reducing the impact of special interests on the election process--while reassessing how to get there. In recent years, Common Cause has focused on two specific proposals: federal financing of congressional elections and limits on total campaign spending. The goals are laudable but the legislation is not.

Republican opposition to federal financing is deep-seated and unlikely to change. That is partly because Republicans have had more success in raising money from individual contributors. But there are other objections as well: For one thing, I don’t want my tax dollars used to elect a David Duke or an Oliver North.

Those who advocate taxpayer funding of elections begin with the premise that private contributions to campaigns are somehow tainted. But our greatest political problem is not excess participation but citizen apathy. We should be encouraging citizens to participate by seeking office, volunteering on campaigns and contributing to candidates who share their views. The evil is not in the individual contribution but in the ability of the wealthy to put so much money into a campaign that they can determine the outcome, a danger that was effectively eliminated by the adoption of strict contribution limits (no individual may donate more than $1,000 per election to any candidate).

Limits on total campaign spending, if not matched by limits on the cost of campaigning--advertising, postage, printing--will merely reduce the ability of candidates to get their messages to the voters. The result will be an uninformed electorate.

Instead of choking off participation and debate, Common Cause should concentrate on increasing the role of the ordinary citizen. One way to do this is by restricting contributions by special-interest political action committees to $1,000 per election cycle, instead of the current $5,000, and restoring tax write-offs of up to $200 for contributions by individuals. More individuals will participate, while large-scale contributors will have an incentive to limit donations to the amount of the tax credit.

To increase responsiveness to constituents, campaign laws should require congressional candidates to raise at least half of their funds from individuals who live within the district, reducing the influence of out-of-state interest groups.

Finally, Common Cause should explore means of increasing the number of public debates and cost-free outlets for the dissemination of campaign platforms.

Fred Wertheimer has led Common Cause to significant victories, but his departure opens the door for new approaches. In less than 90 days, a new Congress will take office. Now is the time for Common Cause to re-examine its strategies. If it accepts new means of achieving its goals, it may yet lead the way to serious election reform. And while it may not come in the form he envisioned, it will be reform that owes its passage to 24 years of Wertheimer persistence. And that beats a gold watch any day.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.